School of Rock

for Bay Nature.jpg&w=633&zc=1)

I first came to understand the rock called Northbrae rhyolite on a sunny afternoon 17 years ago. I was a bored and dorky teenager looking for adventure, and I had taken up rock climbing at a small city park in the Berkeley Hills called Indian Rock. I was milling about with a few other climbers when a muscle-bound crowbar of a man with long black hair and dark features approached me and offered to show me a climbing route–he called it a “problem,” climbing jargon for short ascents done without ropes. He led me to the highest point on the rock where, though the climb was short, the fall to the ground was two and a half stories.

As a gangly kid still waiting for my voice to change, I was awed as this chiseled daredevil traversed the rock face, casually defying gravity. So I followed him. Halfway through I realized I had bungled the sequence–put my right hand where my left should have been. I panicked, froze, and began to shake. Tenuously, with my feet hanging over a leg-breaking fall, I scrabbled my hands into different positions and somehow finished the problem, pale and trembling.

“Cool, right? Kinda tricky in the middle there, huh?” was all he said.

I later learned my long-haired mentor was Dan Osman, a world-famous rope-free climber who eventually died in a tragic (if predictable) accident. And though I never did that problem again, it turns out that I was not the only confused kid who found purpose and guidance on those rocks. In fact, two groups of Bay Area pioneers have visited these and other related rocks for over a century, squeezing from them lessons about discipline, strength, and how to observe the natural world.

If you have been to the Berkeley Hills, you have probably seen Northbrae rhyolite. It’s in the rock walls and the distinctive pillars marking street corners. In some cases it appears as a dishwater blonde rock seeming to grow right out of the side of a house. The most distinctive example, though, is Indian Rock in the middle of North Berkeley.

Rhyolite forms from a viscous sort of lava belched from very explosive eruptions. Berkeley rhyolite comes from two eruptions that happened about 9 and 11 million years ago–one in the Berkeley Hills and the other probably somewhere near what is now Fremont. Each eruption left thick layers of lava, which cooled and were covered by other layers of lava or sediment that were twisted by fault movements with the surrounding darker basalt, like the vanilla in a chocolate/vanilla swirl pudding.

To learn more about these rocks, I joined UC Berkeley geologist George Brimhall one clear fall day on the side of busy Grizzly Peak Boulevard. The view to the west is phenomenal, with a crystal-clear shot of the Golden Gate and Bay bridges splayed out before us. On the other side of the road is a bit of dusty-colored rock about the size of a car jutting out from the hillside–a crumbly remnant of the second eruption 9 million years ago. “This is probably the single most important outcrop up here,” Brimhall says as he takes out an oversize compass. “This has been a training ground, a proving ground, for 106 years of geologists.”

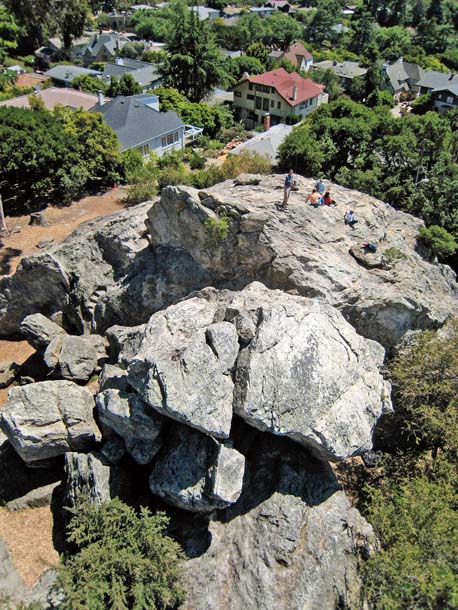

- Kite aerial photo of Indian Rock, the largest of many rocks now incorporated into the residential fabric of North Berkeley. Photo by Cris Benton.

Brimhall teaches a class called Field Geology and Digital Mapping at UC Berkeley. It’s a required course for geology majors and has been since almost the beginning of the university (though the “digital” part is new). With a deep sense of pride, he can recite the course’s instructors all the way back to the legendary Andrew Lawson, considered the father of American earthquake science, the man who named the San Andreas Fault and wrote the definitive report on the great 1906 quake.

But Lawson’s greatest contribution might have been here, in 1891. At that time, Grizzly Peak Boulevard was an old dirt track on an obscure hillside. During class one day, Lawson–then a hip young professor–looked out his window to the hills and said to his class, “Well, that looks fine for geology; what’s up there?” The students grabbed some simple maps and marched up the hill to begin surveying.

For 30 years Lawson would repeat this exercise, dragging his students up every steep ravine and bushy slope to piece together the rock layers. Over the course of the semester, the students would follow this band of volcanics eastward over the hills, searching for spots where it re-emerged, like a giant bookmark in the pages of the surrounding rock layers.

“This is like the cadaver for a physiology class,” Brimhall says. “It allows us to teach students the basic principles of geology, the field skills that allow them to understand how to do this and to be able to work elsewhere.”

This style of “learning by doing” was revolutionary at the time, but it quickly spread. By the time Lawson died in 1952, almost every large geology program in the country had a similar field class. This included one at Harvard, set up by Lawson’s first Ph.D. student, who became the leading mineralogist of his day. Fittingly, his thesis described a band of dusty-yellow rhyolites in the Berkeley Hills.

- A sinuous staircase ascends the southwest side of Indian Rock; the main climbing face is on the opposite side of the rock, which is made up largely of Northbrae rhyolite, formed during a volcanic eruption 11 million years ago. The lava formed a thick layer and later broke up into large chunks. Photo by Ian Creelman.

Geologists aren’t the only people attracted to hard, protruding rocks. The first recorded rock climbing in the Berkeley hills was in the early 1930s by future Sierra Club president David Brower and his friend Dick Leonard. The two were avid climbers and logged many “first ascents” up imposing Sierra peaks, but on sunny weekends, they often gathered with a tight-knit circle of Sierra Club members at Indian Rock to practice rope techniques and flirt with the women in the group.

They were fortunate. Indian Rock was formed from the earlier eruption, which laid down a deeper layer of lava. Unlike Lawson’s outcrop of a thin layer buried in the hillside, the layer of rhyolite that forms Indian Rock got pulled by the Hayward Fault and shuffled “like a deck of cards,” says Brimhall. The layer broke into pieces and left large, exposed boulders for young adventurers to find.

- Mountain climbing pioneer Dick Leonard leaps from Indian Rock in the 1930s. Photo courtesy Colby Memorial Library, Sierra Club.

Mountain climbing then was a Euro-centric, aristocratic endeavor often practiced by wealthy men bored with sailing and polo. This changed in 1933, when Leonard and fellow Sierra Clubbers took their first trip to Yosemite. It was as if someone had carved out a special place just for them. Wherever he looked, Leonard saw thousands of feet of sheer, exposed granite yearning to be scaled. That moment launched the ongoing love affair between mountaineers everywhere and Yosemite Valley. Over the decades, word of this fantastic American climbing destination spread across the world.

Meanwhile, back at UC Berkeley, the field geology course had been taken over by the cantankerous Nicholas “Tucky” Taliaferro, a colorful, sometimes salty professor who once said geology “stops when you get to the Nevada border.” One step at a time, wandering well over 50,000 miles, mostly alone, he painstakingly mapped the rock layers over a piece of California larger than the entire state of Connecticut.

In the classroom, Taliaferro took Lawson’s hands-off teaching style to the extreme. He would walk into the hills with his students, lean back on the head of his axe, stare at a rock, and light a cigarette. The confused students would look around, try to figure out what he was staring at, and start taking measurements. After a bit, Tucky would stand, wander to another rock, and have another smoke. If you missed it, you missed it.

Taliaferro’s mapping was more than just a geologic paint-by-numbers exercise. He was working to solve one of the greatest mysteries in science: What creates mountains and topography? His hard-earned maps showed ancient sand beds high in the hills and volcanic layers at bizarre, impossible angles. He puzzled about this his entire career and constructed a number of explanations, all of which were wrong. He was missing one key piece–the one element that would put California’s jumbled geology into perspective. Sadly, he died in a 1960 car accident just a few years before someone else at Berkeley would help slide that piece into place.

At around the same time, the local rock climbing scene was experiencing a revolution as young, footloose men took up residence in Berkeley while planning forays to the hulking walls of Yosemite. Indian Rock had become a sort of stepping-stone for climbers dreaming of the wild Sierra Nevada in the ’50s and ’60s. Among those climbers were Berkeley locals Galen Rowell and Steve Roper.

“The old cliche that climbing builds character I think is true,” says Roper, who was the first to climb the face of Half Dome in a single day and wrote the first climbing guide to Yosemite. “I’m amazed we lived through it.”

It’s a brisk morning at Indian Rock and I’m standing with Roper near the 25-foot drop that nearly spit me off years before. Using techniques concocted by Dick Leonard, Roper and Rowell would spend their weekends leaping from this platform with an old army surplus cord tied in a loop around their waists.

- UC Berkeley’s first field geology class was taught by Professor Andrew Lawson, who pioneered new methods of teaching geology in the Berkeley Hills. In 2010, undergraduate geology students still map those same rocks. Photo courtesy of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, UC Berkeley.

“We’d anchor ourselves to the tree down there and the rope would come up to the top. Then people would get out on the ledge out there, take maybe ten feet of slack, and jump,” he says.

- Stephen Ference maps chert near Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve. Photo by Mike Kahn/Green Stock Media, greenstockmedia.com.

The game was to see how close to the ground you could get before the rope broke your fall. Even with stronger modern ropes, the thought turns my stomach. In climbing, falling is a necessity but never much fun. Fifty years ago, without harnesses and modern ropes, this backyard bungee would have been near suicide. The game had a practical side, though. With each fall, those holding the rope got better at stopping falls and those climbing became more confident and willing to take risks on longer climbs. Even so, when I ask, Roper says with a shrug that at least once the fun went too far and an ambulance was called for a broken back.

This period is often called the “golden age” of mountaineering and some of the best climbers came from Berkeley or spent their winters here, practicing on local rhyolite while waiting to pioneer new routes on Yosemite’s Half Dome and El Capitan. Then they went on to tackle the toughest peaks in Europe and Asia. Rowell was the first to climb Pakistan’s Great Trango Tower and became America’s preeminent nature and adventure photographer until he died in a plane crash in 2002.

Soon geologists had a revolution of their own. In the 1960s the professor in charge of Lawson’s field geology class was Garniss Curtis, an expert in something called geochronology, techniques to reliably calculate when a rock was formed.

Curtis’s specialty was dating young rocks. Scientists date rocks by tracking how much of an element in the rock has decayed since the rock’s formation. The problem was that geologists were taking measurements using potassium, which takes a long time to decay. “The half-life of radioactive potassium is 1.25 billion years,” Curtis says. “If [a rock] is just a million or two years old, that’s not a lot of potassium that’s decayed.”

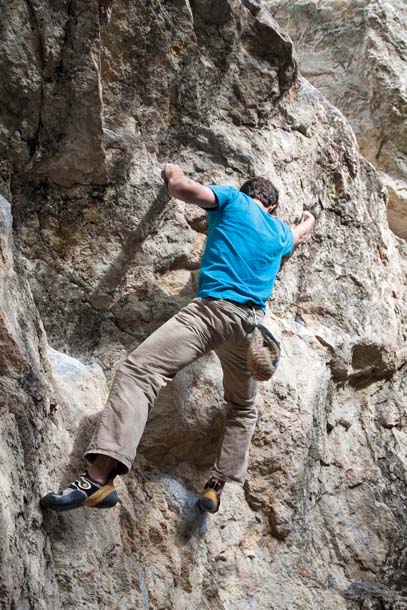

- Ian Walters is one of many bouldering enthusiasts who climb the rocks of the Berkeley Hills. Bouldering is a growing sport that involves low-altitude, highly athletic climbing without ropes. Photo by Mike Kahn/Green Stock Media,greenstockmedia.com.

So age estimates were rough, especially for young rocks. Curtis came along and pioneered a new, more subtle measurement of decay. Using different elements, he was able to pinpoint the age of ash from the fall of Pompeii to exactly the year shown in historical texts. Curtis was even able to date early hominids found in Africa by anthropologist Louis Leakey.

By the 1960s, Curtis and his students were dating all sorts of rocks, including some taken from the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. For decades, some scientists had suggested that the continents might actually move about, like wandering barges on an ocean of magma. Most mainstream geologists, including Curtis, thought this was ludicrous. However, thanks to precise dating by Curtis and his students (all of whom cut their teeth on Berkeley rhyolites), scientists determined in 1964 that ocean floor rocks closer to an underwater mountain ridge in the mid- Atlantic were younger than those farther away. It was as if these rocks were burping out of the ridge and slowly crawling to shore. That insight helped confirm the theory of plate tectonics, and Berkeley became a center for radiometric dating enthusiasts.

Berkeley rock climbers were also changing with the times. Gone were the erudite pipe-smoking philosophers of the mountains; in the 1970s and ’80s, it was sex, drugs, and rock and roll. This new breed was stronger, more athletic, and often intoxicated, and they usually left the ropes at home.

The new fashion was to climb closer to the ground but find the most challenging bits of rocks and work on them over and over until you climbed them successfully. This new sport, called bouldering, demanded that climbers become incredibly strong and–once they began climbing bigger routes–seemingly superhuman. Coupled with stronger nylon ropes, harnesses, and permanent fixtures called bolts, rock climbers looked from afar more like geckos than people.

- Mortar Rock, just east of Indian Rock, is marked with depressions where Ohlone people once ground acorns. Photo by Dan Rademacher.

Indian Rock and now the neighboring Mortar Rock (so named for its Native American acorn grinding holes) were again on the leading edge, with a motley cadre of misfits dangling by their fingertips almost every afternoon. As before, climbers formed a tight bond; grizzled veterans gave advice to younger climbers, shared drinks and, of course, showed off for female climbers.

“It was like a big family. You had some loony relatives and you had people you could be serious with,” says John “the Vermin” Sherman.

There was Nat Smale, the strongest of the bunch (“built like a golf tee,” Sherman wrote in his bookStone Crusade: A Historical Guide to Bouldering in America), and a fan of mind-altering substances. There was David Moss, a meticulously slow climber who never spoke, and Bruce Cooke, who demonstrated one-arm pull-ups off a tree knob into his late sixties.

Today, bouldering is among the most popular of the “extreme” sports. Thousands of climbers flock to places like Bishop, California, to test their mettle against rocks the size of large trucks. They carry thick pads Sherman helped invent and to this day boulderers around the world rate difficulty using the “V-scale.” V, of course, stands for Vermin.

Like pilgrims seeking a shaman, many still visit Berkeley on their way to the Sierra. On a given Saturday, you may see children scrambling about alongside internationally known professional climbers like the late Dan Osman.

Meanwhile, George Brimhall still takes his students into the Berkeley Hills to study the dusty rhyolitic blocks. He says the teaching style is much as it was back in Lawson’s day, with students challenged to find answers in the rock, rather than the classroom. In fact, the Berkeley faculty has a tacit agreement never to publish detailed maps of the hills that might ruin the exercise for the students. A few things are different, of course. The Berkeley Hills “rhyolite” on Grizzly Peak is now classified as the closely related dacite. And Brimhall’s students now use iPad-like devices and rely on GPS tracking. Occasionally, Brimhall worries that a day may come when geology students never even get their shoes muddy.

“A lot of schools now don’t have faculty to teach this kind of a course. They ship students out to geology camps. We still teach our own at a much higher level. Whether or not that’s going to continue I cannot say,” he says, tracing lines on a rock that’s seen 11 million years and thousands of climbers’ hands. “That’s been our Berkeley tradition. It’s a rite of passage.”