The waiter has just about had it. It’s his third time back to the table after being peppered with questions about the cod, crab cakes, and tuna. This time, he notices my menu, marked up like a baseball scorecard with checks, question marks, and exclamation points.

I’m pretty sure the sardines and the squid are OK to order. Sardines grow so fast in the wild, they’re easily replaceable. Squid also reproduce quickly, and according to the menu, these are local, which is good. What I really want is the lobster roll, but I’m not sure that’s the right thing to do.

I realize it’s only lunch, but in fact the decision I make today will have consequences that go far beyond the satisfaction of my personal appetite. Nothing less than the very future of our oceans is at stake.

Global demand for fish has nearly doubled since 1980, and today half the world’s species are currently fished at their limit and another quarter are considered near depletion. Fish that were popular a generation ago, like Atlantic cod and red snapper, are now critically threatened.

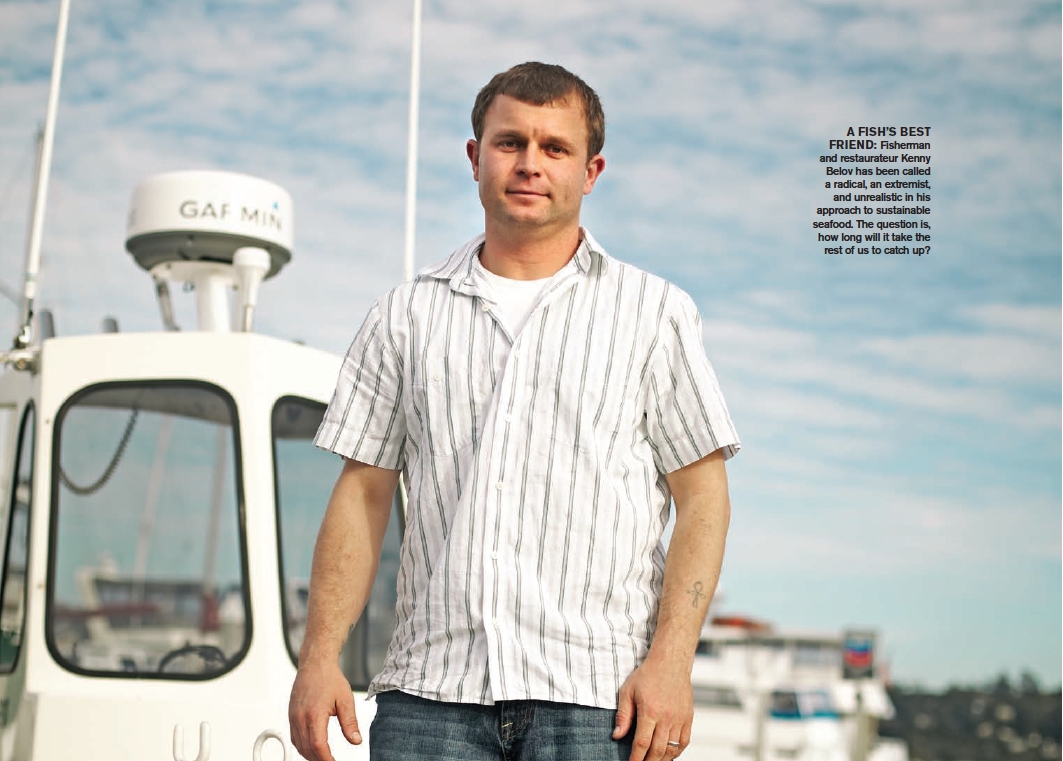

I’ve brought along someone who I hope can steer me to the choice that will do the least harm. Kenny Belov, co-owner of Fish, a seafood restaurant that sits on the dock at the Sausalito marina, and one of the Bay Area’s most strident advocates of sustainable seafood, is helping me make sense of the menu.

It shouldn’t be that hard. The restaurant, Sea Salt in Berkeley, claims to “promote innovative, healthy, and sustainable seafood dining,” so you’d think I could pick anything on the menu and be in the clear, but Belov points out several troubling items. Sand dabs, for instance. The vast majority of these fish are caught by bottom trawlers, which steamroll across the ocean floor and can leave a virtual dead zone in their wake.

The scallops also give him pause. The description, “day boat,” brings to mind hardworking fishermen who head out in their skiffs each morning and come back later the same afternoon, but in fact the scallops were dredged from the ocean bottom with equipment that does considerable damage to the habitat. And the tombo tuna? Belov says no.

“Tombo tuna will become extinct,” he says. “If we continue to catch it with longlines, all tuna will disappear. My lifetime, my kids’ lifetime, I don’t know when, but it’s going to happen.”

In the end, Belov gives the nod to my lobster roll. Although marine biologists quibble, Maine lobsters are fast-growing, opportunistic feeders; their stocks replenish quickly; and they’re caught in traps that aren’t harmful to most other ocean life.

Eating sustainably is at the very core of Bay Area culture, an essential part of the local ethos. Our chefs are leaders of the organic movement, and when we sit down in a top-rated restaurant, we take it for granted that the food we’re served has been sourced with the best interests of the planet at heart. We assume that the salad greens are always organic and that the porchetta sandwich we stand in line for is made with meat from a humanely raised, hormone-free pig who spent his days rooting for acorns underneath an oak tree. But when it comes to offering sustainable seafood, very few local restaurants get it right in any consistent way.

The problem isn’t a lack of interest. There is a booming demand for sustainably caught fish. You’ll find it at restaurants across the price spectrum, from Chez Panisse to (I kid you not) McDonald’s. But at the same time, many of our most famous chefs continue to put unsustainable choices like ahi tuna, monkfish, and farmed salmon on their menus, while their most respected suppliers keep selling red-listed fish to whoever wants it. Even the many chefs who go out of their way to ask the right questions of the people they get their fish from can be misled by the half-truths told all along the supply chain. In the end, despite our best intentions, much of what we’re told or assume about the provenance of the seafood we eat is essentially a fish story.

Belov is one restaurateur who has put truly sustainable fish at the very heart of his business. What separates him from others in the business is a willingness to say no.

Belov is not a local food celebrity or well known in chef circles. Among the fishermen and seafood wholesalers who do know him, he’s seen as someone on the fringe. Colin Lafrenz, a salesman with Ports Seafood, a distributor that supplies many of the Bay Area’s top restaurants, including Fish, admires Belov’s hard-line approach. “Working with Kenny is a whole different ball game,” he says. “Nobody is as radical as he is.”

Belov doesn’t strike one as an extremist. He has the stocky frame and laid-back demeanor of a party-hard frat boy, but in fact he’s a family man who gets up at two in the morning to prepare his fish delivery. He wears baggy shorts and has tattoos on either calf (one of a salmon and the other, oddly, of his former pet chicken).

Belov was born in Moscow, where his parents were active in the art and theater scenes. At one point, his father worked as the director of clowning for the Moscow State Circus.

“Yes, my parents were Russian circus performers,” he says, without a trace of an accent but with a touch of wry amusement.

But the couple chafed under the Soviet system and managed to stir up enough trouble to be “invited to leave.” Belov was five when his family emigrated. He grew up in North Carolina, where he became a devoted fisherman—the kind of guy who spends his nights reading fishing reports as if they were comic books—and a skateboarder (a younger, scrawnier version of him pulling tricks is still on YouTube). At 19, he helped run a successful skate park in Florida; later, he attempted to set up a skateboard store in Moscow, but he backed out when the Russian mafia demanded “protection money.”

He moved to the Bay Area in 1996, where he eventually took a weekend job on a sportfishing boat that operated out of the Berkeley marina. Though he loved the work, what Belov saw bothered him. Boat captains are allowed a limited number of fish on the dock, so they bring in only the biggest catch.

“If a fish wasn’t ‘trophy’ big, it would be thrown overboard, and soon the surface of the water would be covered with dead fish,” he says.

In 2004, Bill Foss, one of the founders of Netscape, opened Fish. Disillusioned by his experience at the Internet company after its startup ideals morphed into what he felt was IPO-style greed, Foss was looking to do something that didn’t require him to give up his principles. Belov started working at the restaurant as a manager on the day it opened. His chummy demeanor, extraordinary knowledge of fish, and antipathy for compromise impressed Foss, and 18 months later, he offered Belov a share of the business, bringing him on board as a co-owner.

Like countless others striving to serve sustainable fish, Belov and Foss looked to the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch list to help them write their menu. Seafood Watch classifies fish as red, yellow, or green according to criteria such as the health of the population, the harm inflicted by the method of harvest, and bycatch—the incidental damage to other species. The list is updated twice a year and printed on wallet-size cards meant to help consumers make responsible decisions about fish.

It’s hard to overstate the impact these cards have had on the seafood industry. The aquarium has distributed more than 35 million to date, plus over 300,000 iPhone apps and an untold number downloaded from their website. Its red, yellow, and green indicators have become ubiquitous in seafood parlance, and many industry consultants and certifiers rely on the list for guidance.

But Belov was not one to be satisfied with ordering fish over the phone, no matter how sustainable its origins. He wanted to be out on the water, bringing them in himself, so he persuaded Foss to buy a commercial fishing boat.

“The idea was to go bring in fish for the restaurant, but also I wanted to see what commercial fishermen did and how they did it,” he says.

On his boat, the Sputnik, Belov’s inner fish nerd ran wild. He hung out with as many fishermen as would talk to him, asking to join them on their boats. (Foss says he’s the only fisherman happy to be boarded by the Coast Guard—so he can talk fishing). He and Foss began to occasionally provide fish and to help a handful of restaurants—places like the Blue Plate and the Flea St. Café. Eventually, his devotion to the sea drove Belov inland, to develop a sustainable trout farm.

There are many ways to catch a fish, but they all boil down to three basic techniques. A fish meets its end by either biting a hook, swimming into a net or a trap, or getting shot by a harpoon or a gun. Two hundred years ago, it was simple: Nets were small, hooks were attached to fishing rods, and the ocean was a big place. Today, the ocean is starting to look much smaller as it fills up with flotillas of 400-foot boats carrying football field–size nets guided by satellites and planes, operating under a sort of aquatic slash-and-burn philosophy.

Industrial bottom trawlers rank among the most devastating types of gear both in terms of habitat destruction and bycatch. These huge vessels drop nets that sink straight to the ocean floor and then drag them for up to 25 miles, collecting whatever is in the way. The nets are sometimes held open by giant doors that can weigh as much as a ton each and crush coral reefs, rocky outcrops, and benthic life as they drag along. When a trawler passes through, a diverse seafloor can be left as smooth as a newly paved superhighway.

After five hours of trawling, the nets come up, the fishermen take what they want, and the rest is tossed overboard. Globally most shrimp is harvested this way, with up to 33 pounds of unwanted fish going to waste for every pound of shrimp brought in.

Longlines are another common, extremely harmful form of fishing. These lines, which can be up to 60 miles in length, are outfitted with thousands of hooks that snare hundreds of animals as bycatch, including dolphins, sea turtles, and sharks.

There are, of course, less destructive ways to catch fish: harpoons, traps, smaller-scale purse seines that use sonar to target schools of fish and bring them up with minimal bycatch, and baited lines trolled through the water behind slow-moving boats.

But the question isn’t if a particular type of gear harms the environment, only how much. Tom Worthington, a partner at Monterey Fish Market, a local wholesaler that’s been a leader in sustainable seafood for over 30 years, insists that even among boats that use nets or longlines, or that dredge shellfish from the ocean floor, there are different degrees of damage being done, depending on the size of the operation and the habitat in question. “Every fishing method leaves a footprint,” he says. “You’re changing the ecosystem no matter how you get the fish. It’s a question of scale.”

Down in Half Moon Bay, the Mr. Morgan, captained by Steve Fitz, is the only boat on the West Coast to use a Scottish seine. Hailed by the Nature Conservancy as “the most environmentally friendly flatfish harvesting method,” this seine is a lightweight net that works a little like a trawler but moves more slowly and with far less degradation to the ocean floor than the large-scale industrial type.

Belov says the Mr. Morgan catches the only sustainable petrale sole and sand dabs in the Bay Area, except for the tiny number that small-timers like him pull in with a rod and reel. (Worthington would add to the list those brought in by lightweight trawlers that drag through sandy portions of the ocean floor.) The Mr. Morgan has growing cachet among local chefs, a few of whom go so far as to list the boat next to a dish on their menus, sometimes even when the fish came from someplace else.

The more time Belov spent fishing, the more he realized that what he read on menus didn’t always match what happened out on the ocean. He began to notice restaurants listing dishes made with trawled or imperiled fish—just inches above the sustainability manifestos printed on their menus. There was the time he was having lunch at a popular downtown seafood restaurant, one that goes to the trouble of listing not just where its fish is caught but also, in many cases, the name of the boat that brought it in. On this day, the menu included lingcod from a fisherman that Belov knows, so he pulled out his phone and made the call. “No, that’s not from me,” said the fisherman. “It’s been two years since I last caught a lingcod.” Belov can tell many such stories.

Josh Churchman, a commercial fisherman who works off the coast of Bolinas, knows that some restaurants named his boat as the source of their black cod several weeks into December. “I haven’t fished black cod since early November. They get the name of a fisherman like me, and they don’t want to take it off the menu,” he says. Once the winter storms begin, many local boats stop bringing in black cod. Any of it on menus from November into the spring is likely coming in frozen from Alaska. “Shame on them in a way,” says Churchman, but he adds, not wanting to rock the boat, “Maybe you should just let a sleeping dog lie.”

“We do our best to be sustainable,” says Scott Gehring, the chef at Sea Salt, who does some of the ordering. “It’s hard.” Gehring says the restaurant no longer sells the dredged scallops that were on the lunch menu I marked up, but they do sell red-listed ahi tuna. And they were selling Lake Huron smelt that actually comes from Lake Erie.

“If you put ‘Lake Erie’ on something, with the reputation Lake Erie has from 25 years ago, what do you think people would do?” says Mitch Gronner, the sales manager at the sustainable fish broker Aloha Seafood, who sold the fish simply labeled as a product of Canada. (As of early January, the restaurant started listing the fish as “Great Lakes smelt.”)

Claims made on menus or by wholesalers are rarely checked or policed. Reports suggest that less than half the “wild” salmon in the markets during the winter months is actually wild, and more than 60 percent of “red snapper” is fake. Gronner laughs and says that in the Bay Area, it’s more like 99 percent. Real red snapper from the Gulf of Mexico goes for about three times the price of the rockfish that often gets labeled as snapper here.

When it turns out that Waterbar’s “reel-caught” black cod was likely snagged by a trawler, it’s not clear whether the restaurant is misleading the diners, the chef is being misinformed by his supplier, or the supplier is the one who has been tricked. Though many chefs have strong relationships with the farmers and ranchers who provide their vegetables and meat, few have similar connections with fishermen.

Melissa Perello, chef-owner of Frances, says that she finds fish the most frustrating ingredient to buy. “Someone may tell me that black cod comes from Fort Bragg, but how do I know if that’s true?” she says. “I wish I could buy my fish direct rather than going through a middleman.”

Beth Wells, a co-chef at Chez Panisse Café, can tell you who grew the lettuces she serves and where the grass-fed lamb she pairs with curry sauce and sweet-potato purée was raised, but says that when it comes to fish, she mostly depends on her wholesaler to do the right thing.

“We’ve had a relationship with Monterey Fish for a really long time,” she says. “We trust what they tell us.”

And so the restaurant owned by the woman who has done more to promote responsible eating than anyone else in the country sometimes offers trawl-caught petrale sole and dredged Atlantic scallops.

Worthington, of Monterey Fish Market, says he makes a priority of finding fishermen who operate responsibly. The sole and scallops he sold to Chez Panisse were brought in with lightweight gear that has minimal impact on the oceans, he says. The overfished Atlantic fluke was also on the menu there not long ago, at a time when it was clearly on the red list. But Worthington wants to support small fishermen who do the right thing by bringing it in on rod and reel.

He’ll sell bottom-trawled monkfish or Australian-farmed hiramasa, both on the red list, if that’s what the customer wants, but meanwhile he tries to push a restaurant toward a sustainable choice. He promotes boats that are somewhat less destructive, though he has a tough time verifying some of the information he gets.

“I’m a business person,” says Worthington. “I have a responsibility to my family and my employees to keep income coming in. If I did what Belov does I’d have nothing but a retail store on a corner in Berkeley.” Working on a larger scale, even with the compromises it sometimes demands, allows Monterey Fish Market to have a louder voice in the conversation and bring reluctant chefs and other wholesalers into the game, he says.

Tracing fish back to the fishermen is a labor of love that few along the supply chain care to undertake. The Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and the National Marine Fisheries Service all theoretically police seafood labeling. But fish dealers consolidate what they sell from fishermen spread across the world, which makes it very difficult to verify how a fish was caught. An astounding 84 percent of American seafood comes from overseas and passes through several brokers and wholesalers before it gets to the dinner plate. Furthermore, the temptation for those all along the supply chain to raise prices by claiming sustainability is huge.

“The challenge of tracing fish, particularly imports, has been recognized not just by the government but also by the industry as being a serious problem,” says Richard Gutting, former head of the country’s largest fishery association and a past legal adviser on the subject to Congress. “A consumer at a seafood counter asks, ‘Where does that fish come from?’ And the guy behind the counter tells him. Well, he’s gotta kind of trust that guy.”

Belov knows firsthand what it means to trust the wrong guy. One of the more popular dishes at Fish was ahi tuna poke. Belov bought the fish from a dealer in the Marshall Islands who was the height of green cachet, claiming he was trolling a line behind his boat and pulling the fish out one at a time. Excited to promote good actors in the South Pacific, Belov planned a trip to visit the supplier. Over the phone, a befuddled employee at first welcomed the idea but then seemed hesitant.

“ ‘I’ve got to go fishing with you. That’s the rule,’ ” Belov told him. “Well, when the plane ticket was about to be bought, the fisherman confessed, ‘I’ve been lying to you.’ ”

The fish were never picked one at a time off a line behind the boat. They either came from a long line or had been indiscriminately netted. Foss says this kind of “greenwashing” is common, especially with tuna.

“Just because someone writes ‘sustainable’ on the package, that doesn’t mean it’s true,” Foss says. “If you talk to people in this industry long enough, you get the feeling that the joke’s on the customer about what they’re selling you.”

Belov was incensed about the tuna, and he took it off his menu. He’ll keep it off until he can find an honest dealer.

“That one was hard, pulling ahi tuna off my menu,” he says, and then pauses. “I had so many people walk up to the fish market and say, ‘What do you mean, you don’t carry it? Mollie Stone’s carries it. Whole Foods carries it.’ ” They assume that if you can find ahi tuna at Whole Foods Market, a store that calls itself the “world’s largest retailer of natural and organic foods,” it must be OK. In fact, Whole Foods recently made a commitment to stop selling longline-caught ahi tuna and all red-listed fish by 2013.

Lafrenz, the salesman for Ports Seafood, also got fleeced on the Marshall Islands tuna. He’s committed to sustainable seafood but says that he has to take a vendor’s word when the fish comes from another country.

“We hadn’t been down there to see it. We just based [our trust] on the quality of the product and the quality of the relationship we had,” he says. “I’m not going to lie to you: It’s probably pretty common.”

One of the biggest problems, from the consumer to the fisherman, is a reluctance to accept that there are limits to what we can take from the oceans. Chefs want to offer popular choices like tuna, shrimp, and salmon, which they know their customers will buy. Fish dealers worry that if they refuse to sell a certain fish, the restaurant will simply buy it from someone else. Lafrenz, a veteran of the fishing industry, says he can’t refuse to sell a chef a particular fish, regardless of its status, and expect that chef to come back. Belov shakes his head.

“Yes, you can. Absolutely you can. Give them an alternative. Don’t be afraid that you are going to lose an account because you said no to a chef,” he says. The key is to match what the customer has in mind with a different fish. Belov refuses to sell petrale sole, a trawl-caught local favorite. But when people ask, he’s always ready.

“ ‘I already know what you want. You’re looking for a white, delicate, flaky fish,’ ” he says. “ ‘Let me take a line-caught Alaskan halibut fillet, and let me cut it down the middle and make it this thin for you. You’ll be able to do the exact same thing with it, it’ll flake apart, it’ll be delicate, and it’ll be sustainable.’ ”

This willingness to say no is key to Belov’s philosophy at Fish, and to his wholesale business, Two X Sea.

Belov knows that cutting a popular fish from a menu isn’t an easy thing to do. By 2010, Fish had let go of two—tuna and petrale sole. But it was the prospect of cutting trout that finally pushed him over the edge.

Rainbow trout are generally considered as eco-friendly as they come. Firmly on the green list, they eat mostly insects. But wild trout doesn’t get served in restaurants very often. Commercial trout, along with about half of all the fish consumed worldwide, comes from farms—essentially ponds or tanks packed with fish that eat dried pellets until they are big enough to sell.

This has led to the kind of problems that give farmed fish a bad reputation. For instance, a pen of hungry salmon produces a lot of waste. Since many farms are little more than fenced-off areas in coastal regions, large concentrations of that waste drift out to sea or collect in estuaries and bays and choke out many species living on the seafloor under the farm.

But the biggest problem with farmed fish is feeding them. Carnivorous fish need other fish to eat: Up to four pounds of wild fish are needed to produce just one pound of farmed salmon. Belov’s nonprofit, Fish or Cut Bait, which encourages restaurants to give up farmed salmon, has pissed off many in the business. Instead of farmed salmon, Belov served farmed trout from Idaho, which he was told had been fed a vegetarian diet.

It turned out that “vegetarian” was a relative term. The truth is that trout eat whatever they can get. Theoretically, they could live on plants alone, but they grow faster when fed other fish, so farmers make feed from a mix of wild fish and plants. It’s not as damaging as what farmed salmon eat (less than one pound of fish meal is needed to produce a pound of trout), but Belov is not one to compromise.

So Belov and Foss—who were already restaurateurs, commercial fishermen, and wholesalers—added “fish farm” to their list of enterprises.

Foss canvassed California trout farms, looking for one willing to try an experimental feed made mostly from algae (Foss and Belov turned their noses up at ground chicken, another favorite fish food). They found David McFarland, a fish farmer 100 miles north of Lake Tahoe, near the Nevada border, and Rick Barrows, who develops fish food for the industry.

Barrows says that what fish need are specific nutrients, not specific feeds. It’s only recently that anyone asked what those might be. It turns out that many exist in seaweed. McFarland started feeding pellets made from algae, corn, and soy to a tank of rainbow trout. The fish did fine.

Over the next few months, the men developed an almost entirely vegetarian trout (the feed also contains some fish oil) to sell at Fish and a handful of other restaurants, like Nopa and Bix. And unlike farmed salmon, which tastes bland and must be stained pink, these fish are healthy and delicious. Recently the men started an experimental program to raise trout on an entirely vegetarian diet. McFarland now grows about 30,000 pounds per year of the state’s only commercial trout that’s not fed fish meal. Foss and Belov plan to develop a similar program for tilapia.

On a cloudy fall day, I pull into Fish for the first time. Belov, who has been up since two in the morning preparing and delivering orders for chefs, introduces me around the airy dining room, where among other customers a few fishermen are eating; the daughter of one of them works in the front of the house. (Farmers and fishermen get half off their bill and are encouraged to answer questions from diners.) It’s late for lunch, but the place is packed. Belov brings over some beers, a halibut Reuben for me, and a couple of fillets of his new algae-fed trout for himself. The prices are steep—a sandwich made with line-caught wild Alaskan salmon goes for $22—but Belov and Foss try to keep costs in line. The tables are simple and there are no servers, but when I taste the food, I don’t really care. Although I have never been a big seafood fan, I eat my entire sandwich and most of Belov’s trout while he talks fish.

“Am I too extreme? I don’t know. I don’t think so,” he says as I raid his lunch. “I don’t find myself very radical. I think of myself as trying to do the right thing.”

It’s hard to argue, with bits of the halibut sandwich staining my shirt. However, many of the people I talked to said that Belov’s rigid take on fish is unrealistic. He regularly irritates other restaurateurs and dealers. Most of them say you can’t dictate sustainability but instead have to work it in slowly, taking baby steps and accepting that there will always be gray areas. But that’s not how Belov sees it.

They say that the meek shall inherit the earth, and the way things are headed, it looks as if they’ll be getting the oceans as well. Like old redwoods, big fish have become increasingly difficult to find. Massive swordfish—300 pounders—were once the norm, with record fish weighing three times that much. Today, 70- or even 50-pound fish—not yet old enough to breed—are considered a decent catch. Other big predators, like marlins, sharks, and dolphins (already down 90 percent by some estimates) will soon be found only on sports uniforms. And we’ll be looking for recipes for jellyfish, which will be everywhere, once the predators have disappeared.

“The fishing industry seems to be the hardest-working industry on the planet at putting itself right out of business,” says Sheila Bowman, senior manager of outreach for the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch, echoing a common sentiment. “They’ve been a bit shortsighted.”

Americans are voracious, but not particularly adventurous, when it comes to seafood. Ten types of fish account for almost 90 percent of our consumption. Just three of those make up 55 percent: shrimp, canned tuna, and salmon.

“If we could stop eating those three and start spreading our demand among the several hundred other species, the condition of our oceans would get a lot better right away,” says Bowman.

Though Belov and Bowman clash on certain issues (he wants to ditch the whole yellow list), she admits that most of the people in her office agree with him down deep. “If we all had our way here at Seafood Watch, we would be more like Kenny,” she says.

Back at Fish, Lafrenz has come to chat about the opening of the crab season. California Dungeness ranks as one of the most sustainable of all local fisheries, and from November through May, Fish turns into a crab processing plant at night, with seasonal workers cracking the crustaceans and pulling out their meat. Belov oversees the operation. “It’s been officially proven that I’ve lost my mind,” he says, grinning.

“I don’t look at myself as a game changer,” he says, “or think that I’m going to fix the world’s problems. I know I can’t. But I sure

as hell can do my part. And if I can convince enough people to work with me, maybe I can do a little more.”

In the end, if some shred of ocean diversity is to be preserved, distributors, chefs, and consumers must all play some part. The distributor errs when he agrees to sell a red-listed fish, chefs screw up when they turn a blind eye to the origins of what they serve, and consumers blow it when they insist on satisfying their appetite for a particular seafood regardless of the environmental costs.

We all need to know more, but it’s too much to ask the general public to keep tabs on an entire planet’s worth of fish. Some federal guidance on what qualifies as sustainable seafood, whether it’s wild or farmed, is necessary. And standards must be monitored through the entire distribution chain.

Restaurants must be held accountable for the claims they make on their menus. Sustainability has to be more than a marketing gimmick, especially when diners are paying for it. One model might be the LEED certification: Certain restaurants would receive bronze, silver, or gold ratings, based on the number of steps they take toward a clearly defined standard.

Lastly, everyone at every step along the way has got to ask more questions. “How was this fish caught?” is the most important one. If the waiter doesn’t know, ask the chef, and if you don’t hear the right answer (and let’s be clear: “I don’t know” is not the right answer), order something else. Let the restaurant know that sustainability matters to you. If enough people start asking the right questions, even indifferent chefs will find their way to people like Belov.

Bowman tells of a restaurant owner whom she was trying to convince to serve more sustainable seafood. “The guy would sell anything that came out of the water,” she says. He complained about the salmon restrictions and refused to remove shrimp from his menu. One night, his six-year-old daughter asked him, “Is the fish going to be here when I’m a big girl?”

He called the next day. “I can’t do this anymore,” he said to Bowman. “What do I need to do?”

Erik Vance is a science writer based in Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Nature, Discover, and the Utne Reader.Additional reporting by Timothy Kim.